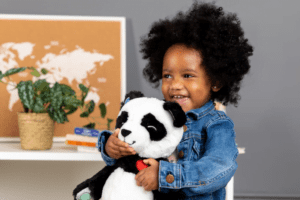

The Importance of Transitional Objects in Early Childhood

As a longtime educator of toddlers and twos and a doctoral student studying transitional phenomena and object relations, I have had the distinct pleasure and privilege to observe parents, teachers and caregivers dedicated to celebrating the presence of transitional objects in their early childhood classrooms.